by George S. Bardmesser

Reading “Democrats Still Haven’t Come to Terms with 2016” by David Harsanyi in National Review, an interesting passage caught my eye:

Nor is there any evidence that Clinton was uniquely hurt by third parties. Democrats might hate Jill Stein, but she won 1,457,218 votes, or around 1 percent of the vote. The Libertarian Party ticket of Gary Johnson and Bill Weld pulled in 4,489,341 votes, a better-than-usual performance for the party driven by antagonism toward the decidedly non-libertarian Trump. The Never Trump McMullin/Finn ticket won 731,991 votes from, one assumes, mostly disgruntled Republicans. Another 203,090 votes went to the Constitution Party, which definitely doesn’t sound like a group that would appeal to most Democrats. In short, if anyone was hurt by third-party candidacies, it was probably Trump.

Being an eternally sunny optimist, I had been thinking for a while about what a Donald Trump landslide versus a Trump squeaker might look like. (I refuse to contemplate the possibility of a Democratic victory.) Specifically, I had been thinking mostly in qualitative terms about the impact of the Libertarian Party on the election, and how things might look different in 2020 versus 2016. Harsanyi’s article got me to try to think about it a bit more quantitatively.

First, a word about the Libertarians. While I am vaguely sympathetic to the principles espoused on their website, e.g.:

As Libertarians, we seek a world of liberty—a world in which all individuals are sovereign over their own lives and no one is forced to sacrifice his or her values.

We believe that respect for individual rights is the essential precondition for a free and prosperous world, that force and fraud must be banished from human relationships, and that only through freedom can peace and prosperity be realized.

I don’t really consider this (and the rest of their “plans”) a serious political program. Some Libertarian ideas seem akin to supporting good weather—who can possibly be against it? Who could possibly favor force and fraud in human relationships? Some of it, I am more or less on board with, like less government interference in the healthcare and health insurance markets—but I would expect most right-of-center people would be on board with such generic things. Some things are quixotic nonsense, like the Libertarian position on taxes, which is “pay them only if you want to.”

Overall, from the outside looking in, Libertarianism looks like mostly feel-good center-right utopian baloney. Given that Libertarians aren’t exactly thick to the ground in my neighborhood, I am not sure I’ve ever actually met one. I am guessing that most voters who usually vote for a Libertarian for president are discontented Republicans, eccentrics, starry-eyed dreamers, right-of-center idealists of some variety, and a few assorted oddballs.

Having said that, given the ever-more-extreme leftward ideological drift of the Democratic Party (with or without Bernie at the helm), the logic of throwing away your vote by voting Libertarian in 2020, so that a Democratic candidate who is utterly antithetical to everything you stand for can benefit from your vote, escapes me. Logic suggests that every Libertarian who cares about Libertarian principles should vote for Trump (who is no Libertarian, but at least isn’t a socialist either)—but, alas, voting is not always a logical exercise.

The same can be said for the Constitution Party. Also, more or less the same can be said for supporters of the eccentric candidacy of Evan McMullin. They might claim that they are both very different from Libertarians, but, frankly, these are like the differences in post-1917 communist Russia between the Bolsheviks, the Mensheviks, the Trotskyites, the left-wing Anarchists and the Social Revolutionaries. They thought their differences were critical and ideologically significant. To all normal people, the differences were barely comprehensible, and all that mattered was that by the mid-1920’s, all the “wrong” leftists had been shot, and the Bolsheviks ended up doing the shooting.

But, we’re not going to shoot anyone here—we’re just doing some thinking about the future.

Trump won 30 states in 2016. No Trump landslide, not even a tsunami that submerges the country in red, will ever result in 49 states, or even 40 states, in his column. It is simply impossible. California, Oregon, Washington, Massachusetts, Vermont, Rhode Island, Delaware, New York, Maryland, Connecticut, New Jersey, Illinois, Hawaii and the District of Columbia will not vote Republican even if Kim Jong-Un were at the top of the Democratic ticket and Nicolas Maduro were his vice presidential pick.

(The potential Bernie-AOC ticket or Bernie-Stacey Abrams ticket is ideologically not all that distinct from the Kim-Maduro lovefest. It’s a difference of degree, not kind.)

So 13 states plus the District of Columbia are off the table, leaving 37 states—this is the absolute maximum that Trump could possibly win, in a scenario where all the stars and planets in the heavens align just right. In other words, the difference between the Trump 2016 squeaker with 304 Electoral College votes, and a Category 5 Trump electoral storm, is 7 states.

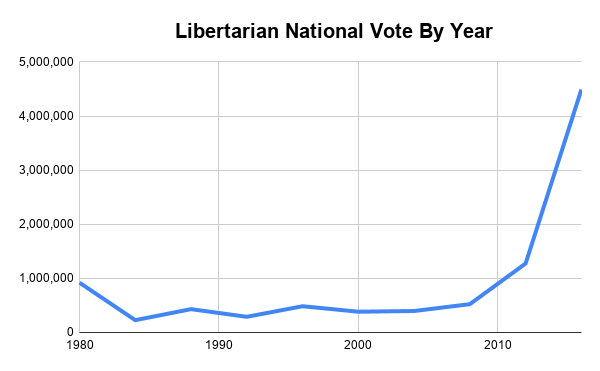

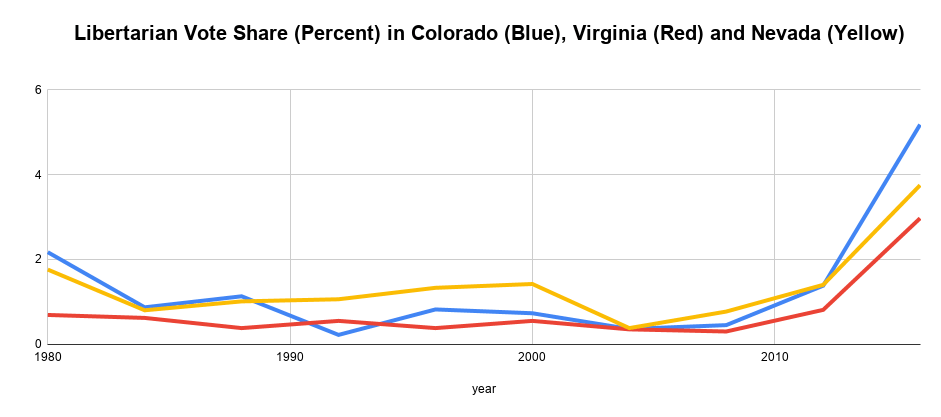

So now we turn to the Libertarians, who performed as follows since 1980:

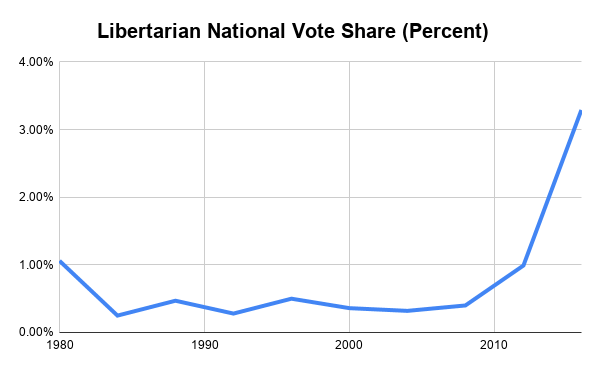

As is self-evident from the graph, 2016 was a spectacular outlier for the Libertarians, when they won 3.3 percent nationally with their 4.5 million votes:

A fraction of a percent is a more typical Libertarian performance—and giving them half a percent is on the generous side. Incidentally, that uptick in the Libertarian vote is the reason Hillary won the meaningless popular vote—were Libertarians performing as they would in an ordinary election year, Trump probably would have been ahead or about even with Hillary in the popular vote.

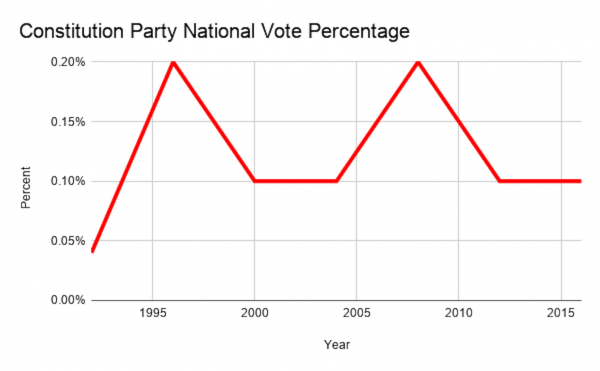

The Constitution Party typically receives even smaller numbers (and 2016 wasn’t a particularly spectacular year for them, with 203,000 votes):

In percentages, they bounce around a measly 0.1-0.2 percent:

If Libertarians aren’t exactly thick to the ground, then a Constitution Party voter is one of those exotic, nearly mythical creatures—I wouldn’t even know where to find one. Then again, in a very tight race, that 0.1 percent just might make a difference—just ask former Senator Kelly Ayotte (R-N.H.), who lost her seat in 2016 by 743 votes, exactly 0.1 percent.

Evan McMullin was a 2016 flash-in-the-pan, who received 731,991 votes nationally, or 0.54 percent. We can safely assume that every one of those votes was cast by a Republican.

For the sake of brevity, and without getting into pointless distinctions, I will simply refer to all of these various groupings collectively as “Libertarians” in the text below. Any reference to the “Libertarian” vote in the discussion of the specific states below includes the other two as well. In some years, the Constitutional Party was not on the ballot in all states. Some states in some years had other fringe parties or candidates, like Pat Buchanan, American Independence Party, etc., that appear more or less aligned with the Libertarians, and which I lumped together with them.

This, if anything, overstates the significance of the Libertarians historically if my lumping of some of these fringe actors together is in error.

From the numbers above, in 2016 nationally, a grand total of 4 percent of voters were Republicans or “more or less Republicans,” who for whatever reason did not vote for Trump but voted Libertarian. This 4 percent is about 3.5 percent higher than their typical 0.5 percent or so performance.

Phrased another way: the unrelenting leftist media attacks on Trump, plus his own… ahem… baggage, like the Billy Bush tape, cost him at least 3.5 percent of the 2016 vote, with over 4 million Republicans voting “near-Republican,” but not Republican. (And that’s not counting Republican voters who didn’t vote at all, or—this is beyond my comprehension, but it surely must have happened once or twice—voted for Hillary.)

The central assumption of this article is that this will not happen in 2020. Generously giving the Libertarians the benefit of the doubt, we will give them their share in either the 2008 or 2012 election in the particular state, whichever is higher.

While the national share is interesting from an overall trends perspective, let’s consider the three swing states that Trump won—Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin—that sealed his victory. How did the Libertarians impact the voting there?

Trump won Pennsylvania by a little over half a percent. The Libertarian share was 2.73 percent. In 2012, their share was 0.87 percent, and in 2008 it was 0.35 percent. Under our generous approach, we will give them the high of 0.87 percent—meaning we add 2.73-0.87 = 1.86 percent to Trump’s totals. In other words, all things staying the same (which, obviously, they won’t), Trump’s margin in Pennsylvania would improve to a fairly comfortable 2.6 percent.

In Michigan, which Trump won by 0.23 percent, the Libertarian vote was 4.1 percent. Under our approach, Trump would win Michigan by a solid 3.6 percent in 2020. Similarly, Trump would win Wisconsin in 2020 by a very comfortable 4.33 percent instead of 0.77 percent.

If true, then all of this means that the three swing states—Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin—would no longer be swinging. With Republican voters moving back to voting Republican, instead of choosing quirky eccentrics as a form of protest or to show existential unhappiness, one can expect that those three states will be firmly in the Trump column even without any landslides, just due to the once newly-minted Libertarians returning to the Republican fold.

Of the seven states that are theoretically in play beyond the 30, Trump lost New Hampshire by less than 1 percent and Minnesota by 1.5 percent. Even a slightly better performance than 2016 would put them in the Trump column. Recall that Trump had approval numbers around 37 percent just before the election. They are now in the 45 percent range even according to Democratic-leaning pollsters that sample registered voters. Thus, no further discussion is needed for these two states.

Then we get to the three more interesting states—Colorado, Nevada, Virginia. Taking a look at historic data for Colorado, Nevada, and Virginia, for example, the Libertarian vote share mirrors what happened nationally:

Trump lost Colorado by 4.8 percent in 2016. Under our analysis, he would win it by 0.2 percent in 2020—on the razor’s edge, yes, but Colorado is very much in play. Trump lost Nevada by 2.4 percent. Under our analysis, he would win it by 0.56 percent in 2020. Trump lost Virginia by 5.3 percent, and under our analysis, he would lose it by 2.1 percent in 2020.

Colorado has been trending bluer recently, as has Virginia. Colorado looks doable for Trump (though it will require a do-or-die get-out-the-vote effort), as does Nevada (a shade more doable). Virginia looks difficult, even with most of the Libertarian vote back in the Republican column. It appears that Virginia is no longer even purple.

New Mexico is an interesting case. Trump lost it by 8.2 percent—normally, an impossibly heavy lift. But the Libertarian vote was 9.5 percent—an anomalously high number. Previously, Libertarians received 3.2 percent (2012) and 0.5 percent (2008). So what to make of this? My sense is that New Mexico is still a very heavy lift, no matter what happens with the Libertarian vote.

Last but not least, Maine is ripe for the picking. Trump lost there by 2.1 percent, but under our analysis, he would win it by 2 percent in 2020 (and would then get three out of Maine’s four electors, instead of just one in 2016).

The Libertarian factor is just one out of many, of course. Every election is unique. A Bernie Sanders nomination (or, for that matter, a Bloomberg one) takes us into some uncharted waters—one can argue either way about whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing, for Trump. I tend to see the arguments in favor of a GOP landslide in a Trump-Sanders match as being more credible, for instance, than any possible arguments in favor of a Bernie victory. But perhaps, like all the pundits who ended up with egg on their faces in 2016, I am only seeing what I want to see.

Each state will have some local issues that might skew the 2020 results, besides the Libertarian-back-to-Republican voters discussed above—Second Amendment issues could (should?) mobilize Republicans in both Colorado and Virginia beyond what most models predict. Energy and fracking issues could (should?) motivate more voters to vote Republican in Pennsylvania and New Mexico—when the other guy wants to put you out of a job, this tends to focus one’s mind better than more abstract concepts.

Same with Michigan—Democrats are no friends of the auto workers, and the GOP must make the case that voting Democratic means voting against your own job. Democrats, similarly, will no doubt try to find local issues that they will use to energize their base beyond what models predict.

With or without local issues, it’s good to know that this factor should put some more wind in the GOP’s sails. The Republican campaign machinery looks like it’s locked, cocked, and ready to rock. Democrats, meanwhile, will be busy going for each other’s jugulars.

I predict that Trump will win the 30 states he won last time, plus Maine, Nevada, Minnesota, New Hampshire, and perhaps Colorado. That’s 34 to 35 states—and that is the outer limit of what a Trump landslide might look like. If someone tells you that a 40-state or 45-state GOP landslide is in the offing, ask him what he is smoking. But I am not too proud to enjoy witnessing a 34-state landslide, if one is on its way.

– – –

George S. Bardmesser is an attorney in private practice in the Washington, D.C. area. He is a contributor to The Federalist and American Greatness, and is sometimes seen discussing politics (in Russian) on New York’s American-Russian TV channel RTVi.

Photo “Libertarian Supporters” by Fibonacci Blue. CC BY 2.0.